About. 900-1100

The settlers brought with them the poetry of immigration. This poem was mainly transmitted orally in the earliest times and is a branch of the Old Germanic poetry, which shows itself in content (preferably in heroic poetry) and form (the dominant use of “langvers” – in Icelandic tradition short verspar – containing four print heavy syllables and are joined by letter strip). The most ancient are the Eddiks. They are about the heroes of the Germanic and Nordic legends and the Norse gods. Most of the heroic poems relate cyclically to the common Germanic legend around Sigurd Fåvnesbane. Most famous of the poems are the two great poems Volus på, where world laughter is produced in powerful visions, and Håvamål, which gives a pointed and pregnant portrayal of pagan life-wisdom and beliefs. It is now common to believe that part of the eddy sealing has come from outside Iceland, e.g. in Norway, but especially the poems that are considered younger, most often the poems in Iceland. See also Edda.

Skaldespiller Poetry

The shell poetry was also brought to Iceland from outside, primarily from Norway, but received a particularly rich flowering in Icelanders. Most of the surviving shell poetry is created by people we know the name through saga literature. The term dragonfly on the most widely used skalders target shows that the skalding arts preferably belonged to the chieftains. The Herds are poems about and for kings and other great men in Norway, Denmark, Sweden and the British Isles. Particularly well-known princesses are Hallfred Vandrådeskald at Olav Tryggvason, Sigvat Tordsson at Olav the Holy and Arnor Tordsson and Tjodolv Arnorsson at Harald Hardråde. This lyrics is very artful, but often stereotypical and impersonal. More sensitivity and personal touch can be found in the many individual stanzas (lausavísur) and in the memoirs of the deceased. The highest may have been Egil Skallagrímsson reached in the famous poem Sonatorrek (Sønnetapet), which sprang spontaneously out of the deep grief of the bald. Some strophes with erotic content have also been handed down, even though such poetry was prohibited by law.

1100s

Iceland has no surviving rune inscriptions older than from ca. 1200. Latin writing came into use when Christianity was introduced in the year 1000. In the beginning, what was written must have been books in Latin for ecclesiastical use. The first to be written in Icelandic was the pedigrees and laws ( Hafliðabók, 1118) and religious texts. The oldest preserved original text in Icelandic (c. 1150) contains fragments of two sermons, and throughout the period there was constant translation (usually from Latin) or recasting of legends (saints’ sagas) and sermon texts. In the 12th century, European influence dominates in all fields of Icelandic literature. Iceland’s foremost men are keen to seek education on the continent. The knowledge of foreign history writing must have helped to strengthen interest in Iceland’s own past.

The oldest historical work handed down is Are Frode’s Íslendingabók, probably written in the 1120s. His style is heavy, characterized by Latin models, but sober and factual. In the section on the introduction of Christianity, however, the seed of the subsequent period’s saga is marked. It is possible that Are was also the first to collect material for the great work on Iceland’s settlement, Landnámabók. The ancient and intimate cultural connection between Iceland and Norway led early on that the Icelanders also authored works on Norwegian kings.

Iceland’s incorporation into the Norwegian church province when the high school was established in Nidaros must have served to bolster Icelanders’ interest in the Olav cult. It is precisely at this time, supposedly in 1153, that Iceland’s foremost bald man of the time, Einar Skulason, utters the famous quadruple Geisli (ray) in Christ Church in Nidaros in the presence of the three royal brothers and the archbishop. The poem is a praise of King Olav as the saint and wonders. In Norway, a legend was written about Olav in Latin. In the second half of the 12th century, the oldest versions of the Norse saga about Olav the Holy are then written. We still have a grips version and fragments of the oldest saga. Here, the Norwegian ecclesiastical tradition of Olav as a saint is united with the Icelandic bald tradition of Olav as earthly king. In the period before 1200, two monks at the Þingeyrar monastery in Northern Iceland, Odd Snorrason and Gunnlaug Leivsson, also wrote their own story about Olav Tryggvason in Latin; later they were translated into Icelandic.

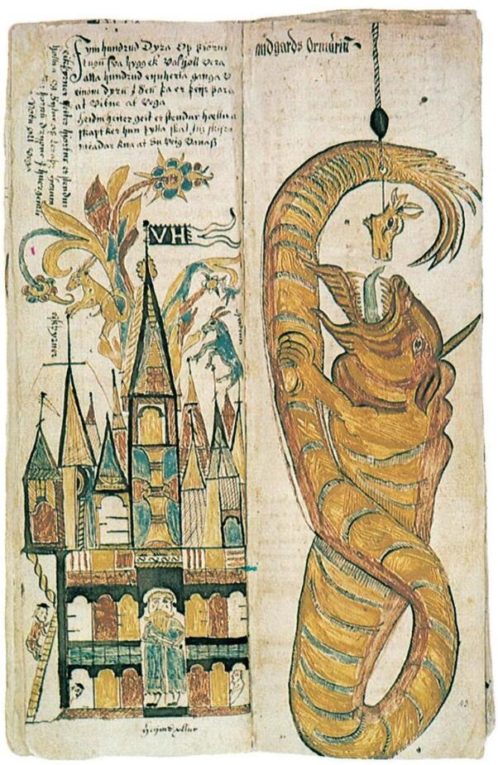

Illustration with Valhall and the Midgard worm of the god-squared Grímnismál in the Elderly Edda. Icelandic handwriting from the 17th century.