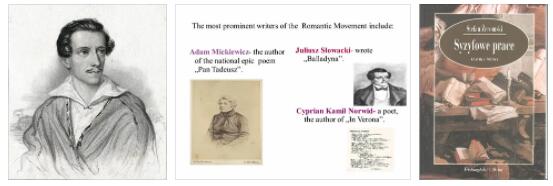

In the double essence – on the one hand the anguished relationship between individual freedom and national freedom, and the religious sublimation of both in the universe; on the other hand, the messianistic conception of the Polish nation and its mission in the world – Polish romanticism is profoundly autochthonous, because it is due to the special spiritual conditions in which Poles, and especially those who emigrated abroad, came to find themselves between the two revolutions: between 1830 and 1863. But, of course, it does not end in poetry alone: alongside poets there are not a few narrators (Michal Czajkowski, 1804-1886; Józef Korzeniowski, 1797-1863; Henryk Rzewuski, 1791-1866), historians (Joachim Lelewel, 1786-1861), critics (Maurycy Mochnacki, 1804-1834) and philosophers (August Cieszkowski, 1814-1894, Karol Libelt, 1807-1875). The younger poets, at least in part, follow in the footsteps of the great romantics: Wincenty Pol (1807-1872), Teofil Lenartowicz (1822-1893), Kornel Ujejski (1823-1897) and not a few others, while movement the greatest Polish playwright Aleksander Fredro (1793-1876), the original poetic agitator of social problems Cyprjan Norwid (1821-1877) and the very fruitful novelist Józef Ignacy Kraszewski (1812-1887).

With 1863 – the year of the second revolution – the second great period of Polish literature can be considered closed. Thirty years of poetic exaltation, often exasperated, are followed by thirty years of “de-intoxication”, of rapprochement with reality, of “positive”, “organic” work around the many problems that were most urgent in tripartite Poland. This post-revolutionary period is also dominated by patriotism – and the identity of the keynote will make the detachment from the art of the previous generation less sensitive – but the way is different, as we now understand the obligations of literature towards the homeland. In addition, the fact that romantic literature was largely the work of emigrants and that it necessarily reflected states of the spirit of someone who had had to, or had preferred, to leave their homeland; while now in Polish culture, continuing also the work – poetically more modest, but culturally no less effective and in any case better corresponding to local needs – carried out by those who had remained in the lands subjected to Prussia, Russia and Austria, new in the two capitals, Warsaw and Krakow, and takes up an address which, apart from the exceptional political conditions, it can be considered normal. Censorship, especially in the lands subjected to Russian domination, naturally made its weight felt on every literary manifestation with a political background; but the writers of the time often managed, with great skill, to elude it with skilful technical disguises. especially in the lands under Russian rule, it naturally made its weight felt on every literary manifestation with a political background; but the writers of the time often managed, with great skill, to elude it with skilful technical disguises. especially in the lands under Russian rule, it naturally made its weight felt on every literary manifestation with a political background; but the writers of the time often managed, with great skill, to elude it with skilful technical disguises.

According to BEHEALTHYBYTOMORROW, the new current did not immediately create its own program, and it was only between 1871 and 1873 that the very young Aleksander Şwiętochowski (1849, alive) published a series of articles that were received with enthusiasm and considered as programmatic manifestos of the “young”. Prose could naturally adhere better to the ideals of spreading culture and educating the masses than poetry; and in fact, if one leaves aside the poets Adam Asnyk (1838-1897) and Marja Konopnicka (1842-1910) who also, inasmuch as their essentially lyrical temperament allowed them, had enthusiastically placed themselves at the service of the new postulates, predominate in those decades of prose writers: storytellers in Russian Poland, historians in Austrian Poland.

Eliza Orzeszkowa (1841-1910) and Bolesław Prus (1847-1912) stand out among the novelists and short story writers: keen observers – especially the Prus – of reality, both rich in a deeply human sense for the humiliated and oppressed, and sensitive to every change and progress in life forms, especially in the female world. Close to the Prus is the patient and penetrating investigator of man and nature Adolf Dygasiński (1839-1902); similar traits with the Orzeszkowa has Marja Rodziewiczówna (1863, alive). They detach Enrico Sienkiewicz (1846-1916), who with his great historical novels glorifying the Polish past wants to hearten his compatriots and keep alive their faith in a better future, and Józef Weyssenhoff (1860-1932), a refined ironist and delicate interpreter of the native landscape.

As in other countries, so also in Poland – and here if ever more radically than elsewhere – the end of the century moves to the attack against positivism. The ideals of romanticism are back in vogue, carried by a fresh wave of spiritualism. Feeling is once again opposed to cold reason, the right of the individual to every kind of collectivism, to science the faith, to the analytical observation of the external world, the investigation of the soul and intuition. All this definitely favors a revival of poetry, undermined by positivism from its already dominant place; and of a poem that is an expression of exceptional moods, of a refined feeling, of a harvest to meditate. The outward form, to which the utmost care is again given, must accompany, to highlight every more subdued and more delicate thrill of poetry. A flexible instrument, agile in the hand of the poet, must be speech and language in general. The torment of creation is considered salutary.