The Yugoslavs, or southern Slavs, from Central Asia, entered the Balkan island towards the seventh century after Christ. There were many tribes that made up the Yugoslav people, but they were all united by the same language and the same customs. Soon, however, they shared and also changed their common characteristics. Each of these groups occupied an area and often had to fight with the neighboring group. The main groups, represented by the Serbs, Slovenians and Croats, had to fight long and for centuries against their enemies.

The Serbs, who had formed their first state in Bosnia and Herzegovina, had their dealings against the Turks and Bulgarians. Among their most valiant leaders, Stefano Nemanja stood out particularly.

The Slovenes, however, had to fight against the Habsburgs and then ended up subjected to the Austro-Hungarian crown until 1918.

The Croats had difficulties with the Byzantines but managed to remain independent for about three centuries. Then, however, in 1102 they were defeated by the Hungarians and they too had to submit to the winners until 1918.

After the year 1000 only Serbia was independent and the history of Yugoslavia was identified with its history. The most famous Serbian king was Stephen Ouroch IV who, defeating the Byzantines, took away from them Thessaly, Albania and Epirus; then he defeated the Bulgarians and also occupied their land.

The king, who was called Dusan, continued his conquests reaching Macedonia and then went against the Turks. He won the first battles, came almost to Constantinople, but suddenly died, at only 46 years old, on December 20, 1355 and his army completely fell apart, so his reign, which by the various Greek and Albanian leaders, was divided into 24 small statues. It was their downfall because the Ottomans, in far greater numbers, began a violent counter-offensive and in 1389 there was a real carnage in Kosovo: 35,000 Serbs died. The Turkish tide swept and Turkish domination over the Serbs lasted from the 15th to the 19th century.

After Kosovo there were many revolts by the Serbs but all of them were useless. In time, the Yugoslav peoples understood that only the unity of all could restore their freedom and, finally, in 1804, with the decline of the Ottoman power, the good opportunity arose for the recovery. And in Belgrade the revolt broke out, led by Giorgio Petrovic, called “Karageorge”, that is “George the Black”. Helped by Russia, also in war against the Turks, they were victorious in the first battles and even came to take possession of Belgrade.

But when the peace between Russia and Turkey was signed in Bucharest in 1812, the Yugoslavs remained isolated. Karageorge was betrayed by Miloch Obrenovic and assassinated by him. For this act Obrenovich was nominated “Prince of Belgrade” by the Turks. And the Principality of Belgrade in 1830 was transformed into the Kingdom of Serbia.

One of his most famous rulers, Michele Obrenovic, also attempted to found a real federation of Slavic states, but assassinated in 1868, his project was not carried out.

In the second half of the 19th century, a period of confusion and unrest began in the Balkans. Austria wanted a war between the two states at all costs and the opportunity arose when, in 1914, on June 28, in Serajevo in Bosnia, the Austrian prince Francesco Giuseppe was killed. Austria attacked Serbia. It was the First World War. This ended with the victory of the allies so Serbia brought together all the Serbian, Slovenian, Croatian and Montenegrin and Bosnian peoples into a single “Kingdom of Yugoslavia”. The first king of the new kingdom was Peter I Karageorgevich.

But the union between these peoples, so different from one another for customs, language, culture and even writing, did not last long. Soon the Serbs, who believed they were the strongest part of the kingdom, found themselves in open conflict with the Croats. And in 1941, at the outbreak of the Second World War, with his aggression Hitler decreed the end of the Yugoslav kingdom. King Peter II, who had been elected in 1934, fled with his government first to Athens then to London. Serbia was occupied and Croatia became an independent state under the dictatorial leadership of Ante Pavelic.

But many Yugoslav patriots decided to continue fighting for the freedom of their country and retreated to the mountains and to any other place where they could organize themselves into groups of “partisans”. These, under the command of Josip Broz, a communist, called “Tito”, helped above all by the Russians, managed to organize a real army which, first, served to control the German offensives and then to attack. This was called the “ghost army” and gave the Germans a lot of trouble. When Nazi Germany collapsed, that army entered Belgrade together with the Red Army.

On 11 November 1945 the Yugoslav Constituent Assembly decreed the end of the monarchy and proclaimed the Communist Republic, of which Marshal Tito was president.

And in this country where everything had to be redone, the Communist Party, with which there was a totalitarian regime, found ample outlet. Belgrade, in October 1947, was chosen as the seat of Cominform, the body that united all the satellite states of the Soviet Union.

Relations with the West became increasingly difficult and vibrant protests were raised by Yugoslavia when, in March 1948, the Allies decided to return the “free territory” of Trieste to Italy.

But even those with the Soviet Union were interrupted because Yugoslavia was accused by Moscow of nationalism, ideological deviation and tolerance of the “kulaks”, ie the wealthy peasant owners. Tito was fiercely criticized for his domestic and foreign policy. Cominform moved to Bucharest and Albania, detached from Yugoslavia, joined the anti-Tito choir.

Yugoslavia protested the accusations made and tightened even more around Tito who, however, continued his adhesion to the Eastern cousins. Cominform never revoked his indictment.

Then the various Soviet officials, present in the country as technical collaborators of the Yugoslav recovery, left the country together with about 10,000 other people. And as the recovery of the nation made use of supplies of Polish steel and coal, Romanian oil, Czechoslovak and Russian machinery and cars, all Cominform countries stopped trade relations and, therefore, supplies. Moscow declared Yugoslavia “enemy and traitor of the Soviet Union”.

At the same time, agreements with Great Britain and the United States were forming in the west; in 1948 the Federal Reserve unlocked the $ 47 million gold reserve deposited by the Yugoslav government in exile; another major credit of 70 million dollars was provided by the United States in 1950 and in that same year they sent a large quantity of wheat to Yugoslavia, plagued by a very serious famine. Then, from 1951 to 1955, over half a billion dollars in military aid came, again from the United States, along with other services from Great Britain and France. Industrial agreements were also entered into with Italy. And all without Yugoslavia being asked for a change in its policy.

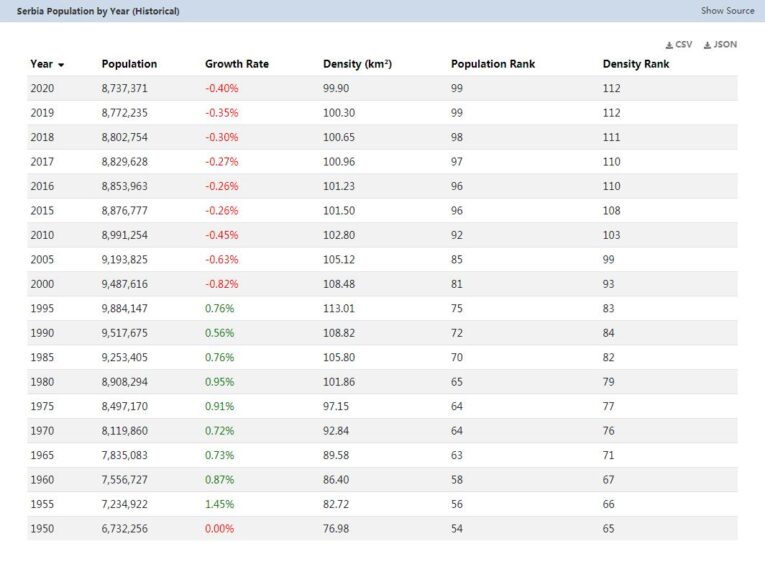

When Stalin died in 1953, Khrushchev and Bulganin decreed the thaw between the two countries and disavowed Stalinist politics. Nevertheless, Yugoslavia maintained its position of “equidistance” between the two blocs. In June 1956 normal relations with the Soviet Union resumed, which recognized the ideological principles of Titus. See Countryaah for population and country facts about Serbia.

Yugoslavia continued to carry out its policy and Tito, in January 1959, visited several countries, such as Indonesia, Ceylon, Burma, Ethiopia, Sudan and the United Arab Republic. Visits that were returned to seal the friendly relationships established. There was also an exchange of visits with Italy: in Belgrade in November 1959 by our Undersecretary for Foreign Affairs A. Folchi and that in Rome by the Yugoslav Foreign Minister V. Popovic. Economic and cultural agreements of great importance were signed.

The crisis between the Soviet Union and Yugoslavia had greatly strengthened the power of Tito who, although a communist, exercised a government tolerant of opponents. What developed most in the country was the desire to level out all the nationalisms present in the various republics and their economic development which, for a time, was greater in Slovenia, Serbia and Croatia. Then from 1957 to 1959 investments increased greatly and the most significant economic improvement occurred in Bosnia and Herzegovina, until then the most backward.

Thus there was an improvement in all sectors of industry, agriculture, culture with the construction of many schools and with the fight against illiteracy, then very large in Kosovo and Albania. Always all under the surveillance of the socialist state which, while restoring private property, did not allow the rebirth of the so-called “bourgeois class”.

On October 27, 1960 a Federal Assembly was called which decreed, among other things, the close link between the wages of individual workers to increase the productivity of companies.

On 28 November 1960 Tito promoted a new constitution that was closer to the new needs of the society which was gradually maturing in Yugoslavia in contact with the regimes of the West.

In 1961 the first conference of “non-aligned” countries met in Belgrade; Yugoslavia in that circumstance was very successful by proposing itself as the third force in balance between the two blocs. The second conference met in Cairo in 1964; in it an attempt was made to establish a common market for the “non-aligned”, but without success.

In the meantime, however, relations with France and the Federal Republic of Germany had deteriorated. With France because Yugoslavia had supported the Algerian Liberation Front; with Germany because it not only refused to compensate for war damage, but also because it was suspected of protecting anti-Yugoslav terrorism.

Little by little, relations with the Soviet Union had strengthened and in 1965 they were the first importer of Yugoslav goods. In 1968, however, these relations experienced a deep crisis after the Russian invasion of Czechoslovakia. In 1971 Brezhnev helped solve the problems by visiting Yugoslavia and intensifying the economic recovery with it.

But even before, Yugoslavia had resumed relations with Germany, which proved more attentive to combat “ustasa” terrorism, which is developing on its territory.

A real industrial partnership developed with Italy. The ideological situations towards China and Albania, which had long been controversial with Tito’s policy, also improved.

Meanwhile, within the Yugoslav republics, tensions of nationalist origin were accumulating, which alone showed how much the removal of the economic and cultural backwardness, a principle always professed, of every single republic, would have eliminated forever the particularities and ethnic differences. The first strong sign of this particular state of affairs occurred in 1971/72 when a large part of the Croatian leadership was eliminated in Yugoslavia and there were multiple purges in the state and party apparatuses, especially in Serbia.

The new Constitution, passed in 1974, confirming the high degree of self-government of the republics within the Federation, had the primary task of guaranteeing maximum social and economic, political and territorial integration.