CULTURE: LITERATURE. FROM THE TWELFTH TO THE END OF THE FOURTEENTH CENTURY

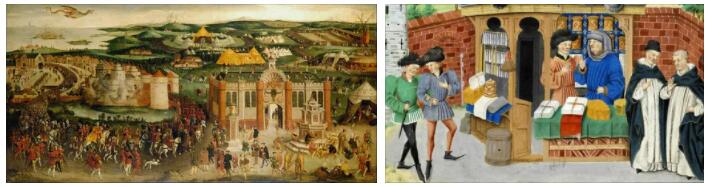

According to Bridgat, capital was also the opening of the “road of San Giacomo”, which for several centuries (from the twelfth onwards) saw thousands of European pilgrims pass by – including, of course, businessmen and travelers, writers and jesters – headed to Santiago de Compostela, which has become one of the centers of medieval Christianity. In this way, while troubadour poetry was widely cultivated in the peninsular courts, also by kings such as Alfonso II of Aragon, Dionysius of Portugal and Alfonso X the Learned of Castile (great and enlightened patron of national culture), the jesters amused the people on the streets and squares; the Church itself, hostile at first to worldly fashions and the use of vulgar languages, came to understand the usefulness of the liturgical representations of Christmas and Holy Week and of the festive recitals of edifying poems. The culture of the Muslim South having fallen and almost disappeared, Christian Spain had, therefore, no small part in the grandiose fervor of rebirth that characterized Western Europe from the century onwards. XI forward.

Among the three main Romance languages, born from vulgar Latin and reached at an artistic level from the century. XII onwards, the Catalan he maintained longer contacts with the South of France (where the Aragonese kings also had political dominions and interests) and subsequently with the Italy of humanism and the Renaissance. The greatest representatives of Catalan poetry were the extraordinary Franciscan mystic Raimondo Llull (Ramón Llull), who died around 1315, and later the Petrarchist lyricist Ausias March (ca. 1397-1459). The lyric flourishing in Galicia (13th-15th centuries) was also important and original, to the point that even Alfonso X of Castile, convinced of the superiority of Castilian over all peninsular languages (and Latin itself), composed the own poems: Cantigas de Santa María (Canticles of Santa Maria). But soon the detachment of Portugal from the Galician matrix, with the consequent beginning of an autonomous Portuguese literature, and the Castilian political supremacy made Galicia a remote province without history. Catalonia, a flourishing Mediterranean state, resisted longer, that is, until Spanish unification (16th century), also giving a first example of a chivalrous romance with Tirant lo Blanch (ca. 1460). But then his literature disappeared, to be reborn, like the Galician one, only in the 10th century. XIX. The overwhelming dynamics of historical events therefore made Castile the axis and the political-civil engine of the Reconquista and therefore of Castilian – the latest of the peninsular Romance languages, but also the clearest, simplest and most open – the dominant language in public documents, in official literature (chronicles and legal texts, such as those compiled by order and under the personal direction of the wise king, Alfonso X, 1221-84), and in the creative one. The first and most interesting phenomenon of the latter is undoubtedly the epic. Apart from the intricate and perhaps irresolvable question of origins (Germanic? Arab? Franco-European?), The epic pathos predominated so much in the primitive Castilian spirit that, after having nurtured several generations of popular jesters – who deserve the credit for having transfigured in epic the historical figure of the Cid Campeador, and not only this -, it permeated the chronicles in prose, penetrated even the learned monasteries (giving rise to the cultured poems of the mester de clerecía), flourished later (XIV-XVI centuries) in the marvelous Romancero – multiform and inexhaustible ” Iliad without Homer ”, according to the famous romantic definition – accompanied the exploits of the conquest of Granada (1492) and the incredible feats of America; and, after the birth of imperial Spain, it still inspired educated poets, playwrights, historical and chivalrous storytellers of the Siglo de Oro, to then go down to the anonymous authors of romances of bandits and gypsies (XVIII century), of Mexican corridos and of Argentine gauchesque poems (also the gaucho is, after all, an epic hero), surviving in the most disparate forms until not too remote times. It is clearly arbitrary to anchor this epic disposition to an unspeakable realism, which would be one of the two fundamental characteristics of the entire Spanish literature (a lyrical and baroque unrealism, with its epicenter in the Moorish South, would be the second). But the grandeur and vastness, in time and space, of the phenomenon is not contestable.

The only surviving almost intact text of the primitive Castilian jester epic is the Cantare del Cid, composed around 1140, whose importance is paramount, even at a European level. But the chronicles bear undoubted traces of other epic cycles: the end of Visigothic Spain, the Castilian origins and the legendary figure of Fernán González, the Seven Infants of Lara (grim story of medieval hatred and revenge, with the Moorish Cordova in the background), the Carolingian legend up to Roncesvalles (with Bernardo del Carpio, a sort of Iberian anti-Orlando) etc.; all themes of great fortune. That of the Cid, for example, reappears in the late Cantar de Rodrigo, now centered on the romance of love with Jimena, in various chronicles, in hundreds of romances and in cultured poems (up to Fernán Pérez de Guzmán and the sixteenth century Jiménez Ayllón), for then move on to the theater. Other themes are legendary (bell of Huesca), or more “modern” history (Poema de Alfonso XI, from the fourteenth century Yáñez). The oldest texts of the Romancero date back to the centuries of the border wars between Castile and the Moors of Granada (XIV-XV century), which later became the most popular genre of Spanish literature (to the point that thousands of romances have been collected by tradition oral not only in all of Spain, but also in America and among the Sephardi, that is the Jews expelled from Spain in 1492). However, soon (13th century), alongside jester poems and sometimes on the same subjects, cultured poetry (mester de clerecía) developed, which has its most representative texts in the Poem by Fernán González, in the fictional ones of Alexander the Great and Apollonius (oriental themes that became European through French poetry) and above all in the religious-narrative poems of Gonzalo de Berceo – the first known poet -, a pious Riojan priest educated in the Benedictine monastery in Spain Millán de la Cogolla died around 1265.

His Miraclos de Nuestra Señora are an excellent example of transplanting the themes of the golden legend to Spain, which were also of great success in fiction and theater. About the latter, only one surviving fragment of the Auto de los Reyes Magos (Auto of the Magi), attributed to the century. XIII, shows that it was a genre of French derivation. In the Spanish Middle Ages, nothing suggests the fabulous prestige that the theater would have had from the sixteenth century onwards. In the sec. XIV the most salient feature of Castilian literature was the Mudejarization, that is the fusion, in original synthesis, of data and genres of oriental matrix with European data: in essence, a sort of cultural hybridization. Two exceptional personalities emerge: a mysterious Juan Ruiz, archpriest of Hita, who died around 1350, and Prince Juan Manuel (1282-1348), grandson of the great king Alfonso X the Learned. Under the name of the first we have received a very unique lyric-narrative-satirical work, the Libro de Buen Amor, still the subject of critical controversies, but in any case of exceptional artistic and cultural importance and certainly one of the most original works of the entire European Middle Ages; the second left a vast work in prose, narrative and historical, culminating in the Libro de Patronio or Conde Lucanor (Count Lucanor), a series of moral tales, “framed” in the oriental way and narrated with a “princely” gravity, not without some ironic variegation that reveals, in addition to the moral one, the artistic intention. A contemporary of Boccaccio and G. Chaucer (whom he certainly did not know), Juan Manuel is the third founder of European fiction. The first humanistic influences, felt especially in Catalonia, and more concrete political-civil concerns for the European and Spanish crises (the Hundred Years War, the great Western schism, the tragedy of King Peter I the Cruel) are variously reflected in others – and minors – writers, such as Rabbi Sem Tob (c. 1296-c. 1369), author of grave and stoic Proverbios morales, and Chancellor Pedro López de Ayala (1332-1407), whose Chronicle of the kings of Castile, more than the long poem Rimado de Palacio, of a didactic-moral character.