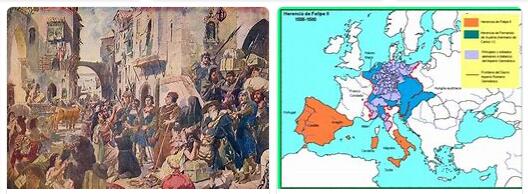

On the other hand, while he accepted for his own reigns the decrees of the Council of Trent (12 July 1564), adhering to the political traditions of Ferdinand and Charles V, he kept the Church under the direct control of the State and indeed increased the power of the monarch. in ecclesiastical affairs.Moriscos of the kingdom of Grenade, which Christian Spain, once again revealing its inability to absorb, had failed to assimilate: at first it tried to convert them to Catholicism, forbade them the use of the language and national dress and imposed new habits and new costumes; and then, being the Moriscosrevolted with the courage of desperation and with savage fury, he ordered that force be used, and Don Giovanni of Austria, whom he had charged, put their lands on fire and, interning them, dispersed them in Castile (1568). Absolutist tendencies followed in the government of the other states belonging to his crown, with the aim of giving them a Spanish soul: in Naples, where the Marquis of Toledo had done much in the previous years, so that autonomy was no more than a I remember; in Milan, which saw the Spaniards settle in the highest positions, previously entrusted to the Milanese; especially in Flanders, which had reduced their innumerable and vast freedoms. And, in the first half of his reign, he also gave a purely national Spanish character to foreign policy. To strengthen the peace with France he married Elizabeth of Valois, daughter of Henry II, in a third marriage in 1559, and to make difficult a possible offensive return of the traditional enemy of Spain and take away value from the Franco-Scottish league consolidated with the marriage of Maria Stuart with Francis II, kept friends with Queen Elizabeth although she was not Catholic and, moreover, she was sovereign of a country that already many reasons of contention separated from Spain, and in secret she gave aid to the rebellious Calvinists to the Stuarts against the Catholic friends of France. He gave the Turks no quarter, not allowing himself rest in the struggle that his religious ardor as a Catholic king and the less mystical desire to free the Mediterranean from guests so dangerous and so averse to a Spanish expansion kept constantly awake: Malta was saved by Don Garcia of Toledo, Marquis of Villafranca (1565); the army of the Italian-Spanish league, promoted by Pope Pius V and Philip II and supported by Venice with the entire fleet, under the command of Don Giovanni d’Austria weakened the Turkish naval power in Lepanto (7 October 1571). And then, even in the second part of his reign, when his attention was turned entirely to the enormous struggle he had faced, he even managed to give political unity to the Iberian Peninsula. In fact, on the death of Sebastiano, who tragically died in the battle of Alcazarquivir (1578), and of Henry (1580), the kingdom of Portugal having remained without sovereign, Philip II asserted his rights on that throne as a grandson on the part of the mother of Manuel I the Fortunate and, having prepared the ground for his own succession.

According to THEDRESSWIZARD, but, although reduced to reign only over a part, even if the largest, of his father’s dominions, Philip II considered himself, and was in fact, his only true heir. Without doubt, he never renewed the imperial ideal, which had been so fatal to Charles V; nevertheless he took on the task of defending the dominance over Europe that his predecessor and he had conquered; and also that of supporting the fate of his house: thus making the first beneficial effects that were obtained from the division into two branches of the Habsburg family, carried out by Charles V at the time of his abdication, very little lasting. In fact, he kept his uncle emperor under his control; wanted the archdukes of Austria with him to direct the education and in fact his pupils were those who then began the Catholic revival in Germany; he tried to get his family on the Polish throne and strengthened his kinship ties with the German branch by marrying Anna of Austria, daughter of Maximilian II emperor. Now, the task he had assumed was very onerous, since the Italian dominions were exhausted from past military exploits; Flanders did not hide their discontent with the internal and financial policy of a sovereign who, unlike his father, made himself feel foreign to it; Spain was beginning to experience the sad consequences of wars, which, attracting a large number of valid arms into the armies, depopulated cities and countryside and decreased agricultural and industrial production, already due to the first, insufficient for local consumption, and he saw the evil aggravated by emigration to America; and the financial situation was very serious, which Philip II had tried to remedy in June 1557 with a real bankruptcy, suspending payments and converting the short-term checks that the creditors had into perpetual annuities or very long-term annuities at 5 per cent on the income of the crown and on which they collected an interest ranging from 10 to 14 per cent: because if, in this way, it is true, he had been able to secure the necessary means to resume the war that was to lead him to the peace of Cateau-Cambrésis, nevertheless it had dealt a serious blow to public credit and exposed the grim state of the state finances.