In this way, thanks to the Catholic kings, Spain, which still largely lacked it, began to have a modern organization, gave itself a certain moral unity, began its own transformation into a great power. And this “national” policy, as it has rightly been said, continued Cardinal Jiménez de Cisneros, during the regency of Castile, of which he was entrusted on the death of Fernando and awaiting the arrival of Charles of Austria (1516-17), when it came to saving the legacy left by the Catholic kings, threatened internally and abroad, and especially to preserve the unity of the state. Contrary to the levers and the allistamenti of people gathering, he organized a real national militia which under him was an element of order; entrusted local administrative offices to competent authorities; he rearranged finance with profound competence; it stood up to the numerous attempts made by the Flemings to seize power; he curbed the opposition of the nobility which in vain plotted against him, imposing himself at the Casa d’Alba, supporting the thesis of the submission to the crown of the three military orders; he suppressed the revolt in Málaga, in Valladolid, in Burgos, in León, in Salamanca, in Villafrades; vigorously repressed the attempts made by the Albrets to restore their power in Spanish Navarre; he reduced the successes of the Muslim arms commanded by Ḫair ad-din Barbarossa, continued King Fernando’s foreign policy towards France and England and defended the Spanish possessions in Italy; facilitated the task of Alfonso of Aragon, left by his father as regent in Aragon.

But the accession to the throne of Charles of Habsburg marked the end of this policy and the beginning of a new era in the history of Spain; the announcement gave him the immediate removal from his position in the Cisneros, immediately ordered by the prince.

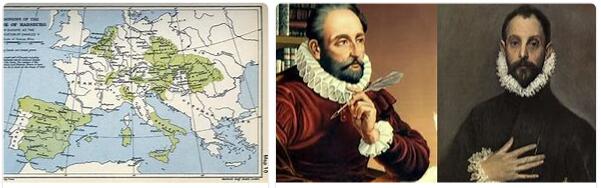

According to SOURCEMAKEUP, the beginning of the government of the new sovereign was stormy: the country, whose self-love had been exalted by the glorious successes of the Catholic kings, did not see the Flemings who accompanied Charles, led by William de Croy, lord of Chèvres, and who immediately revealed their intention to take over the state. In the Cortes of Valladolid the Castilian cities – whose representatives were the only ones who had the right to participate in the work of the Cortes – imposed their removal, demanded that neither offices nor cartas de naturalezawere granted to foreigners, they begged the sovereign to learn the national language “in order to better understand his subjects and be better understood by them” (1518). Then, at the announcement of his imperial election, the opposition became even more open, as the first acts carried out by the monarch seemed an offense to the dignity of Spain, who seemed to want to give priority to the new title and move away from the peninsula; only with difficulty did the Cortes gathered in La Coruña, after their first useless summons in Santiago, grant him the money necessary to cover the costs of the coronation; and, during his absence, the revolt broke out in Toledo and Segovia, and spread to Zamora, Toro, Madrid, Guadalajara, Soria, Ávila, Burgos, Valladolid, León, etc.,Guerra de las Comunidades, in which the rebels, commanded by Juan de Padilla, fought to obtain extensive municipal privileges and freedoms, the ban on the export of money from the kingdom, the right for everyone to the use of arms, which would have been ‘obligation to own, according to one’s quality. However, the revolt (1520-21) was vigorously suppressed; equally in vain was a revolt with a social background which broke out shortly afterwards against the nobility and the upper middle class in Valencia and Mallorca (guerra de las Germanías, 1521-23); the Castilian nobility sided in favor of the monarch, who seemed to have more luck fulfilling the dream of Alfonso X of León and Castile. And, although since then there was no shortage of Spaniards, such as the cardinal archbishop of Toledo Juan Pardo y Tavera, who tried to distract the emperor from insisting on undertakings that could only give him transitory glory y de ayre, the rest they did: on the one hand, the wars fought against France until 1530, which seemed, and in many respects were, a continuation of those supported by the Catholic kings, because they aimed to defend their Italian conquests and to strengthen the position of Spain in the Mediterranean, and because they allowed the adventurous Castilian soldier to continue to reap laurels on battlefields already largely known to them; and on the other hand, that certain economic well-being which the mercantilist policy of the Catholic kings and the colonial conquests had begun to procure for the country, and which made the military enterprises, also creators of an industry, less feared and in some way useful. of war. In fact, at that time the wool industry had acquired a considerable increase, especially in Toledo, Seville, in Valenza and some smaller towns of Andalusia; the requests for products from the colonies and supplies for the army and the fleet had advanced other industries, increased traffic, especially in the Atlantic ports, made agricultural products more sought after; and foreign merchants had come in large numbers to collaborate with their own capital and with their own personal work in trade, in the exploitation of the mines, especially in banking business. Then, in the years immediately following, even if some of the Spaniards and the Italian councilors did not hide their disappointment in seeing Charles V not pursuing only a Mediterranean policy, necessary for Italy, traditional for Catalonia, Aragon, Valencia and which has become dear also to Castile, which on the coasts of North Africa had been led by Cisneros, and they criticized the to the bitter end that he had waged with France, with Lutheran Germany, with their allies; however, in an attempt to realize his dream of a restoration in the spirit and form of the universal medieval empire, which should have encompassed within it all the principles of Christianity, thecorpus christianum, and to reform the Roman Church in an imperial sense – a dream that then had its confirmation in the other one cherished by Suleiman II the Magnificent of submitting the whole world to Islam – the Habsburg, in addition to its homeland, found itself next to the Castilian nobility, always dominated by that heroic, religious-chivalrous spirit, which had played such a part in its past history and which now imposed on it a deep personal devotion to a sovereign, in whom Burgundian upbringing had nourished feelings and passions that some resemblance they had with her parents, and that she felt close to her even in her boundless love for life and for adventurous politics. Furthermore, he had the unconditional support of the Castilian infantry,, outspoken Renaissance men with vivid bloody lights and shadows. Finally, he could count on the energies of the country, which still enjoyed the fruits of its previous economic well-being and was interested in the imperial policy of its sovereign: because then the silk textile industry reached a development equal to, if not superior, to what it had had. in the best times of Arab domination; international trade acquired a huge increase, favored by the enormous extension of the dominions of Charles V, towards the colonies, Flanders, the major ports of the Mediterranean, the coasts of West Africa; the first shipments of gold and silver began to arrive from America.