The island of Patmos is an important place of pilgrimage. The reason for this is the monastery of St. John, located high above the old town of Chora, as well as the so-called Grotto of the Apocalypse, in which the evangelist John is said to have written the Revelation and the Epistles of John in 95/96 AD. The cave was expanded into a church with valuable frescoes.

Old town of Chorá on the island of Patmos: facts

| Official title: | Old town (Chora) with the Monastery of St. John and the Cave of the Apocalypse on the island of Patmos |

| Cultural monument: | fortified, 244 m high monastery in honor of St. Johannes with a library with around 2,000 valuable manuscripts and 13,000 other documents, including the text of the Book of Job (8th century) decorated with miniatures, the Chora, the settlement with mansions like Kalligás from the 16th to 19th centuries. Century, and the “Grotto of the Apocalypse” with the double churches of St. Anna and St. John |

| Continent: | Europe |

| Country: | Greece, Dodecanese |

| Location: | southwest of Skala on the island of Patmos |

| Appointment: | 1999 |

| Meaning: | an architecturally extraordinary example of a traditional Greek Orthodox pilgrimage center and memory of St. John |

Old town of Chorá on the island of Patmos: history

| around 95-96 | Exile of St. John on the island of Patmos |

| 1088 | Founding of the monastery of St. John |

| 1201 | first directory of the monastery’s church treasures |

| 1207 | Occupation of Patmos by the Venetians |

| 1210-20 | Frescoes in the Lady Chapel |

| 1244 | Trade privilege for the monastery |

| 1453 | Admission of refugees from Constantinople |

| 1537 | Conquest of Patmos by the Turks |

| 1693 | Grave place of Gregory of Kos in the monastery |

| 1912 | Occupation of Patmos by the Italians |

| since 1947 | Part of Greece |

| 1958 | Exposure of the frescoes of the 12th century chapel of Theotokos |

The Isle of Revelation

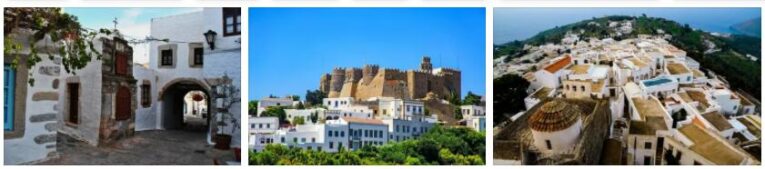

If you approach Skala, the small but lively port city, from the sea, Patmos presents itself with an impressive panorama. High above, the white houses of the Chora settlement shine in the sunlight, in the middle of which the mighty crown of the Johanneskloster is enthroned. She almost seems a little removed from the earthly hustle and bustle down here. And finally, on some summer evenings, spotlights skilfully transform the scene into a film-ready setting.

During the season, cruise ships besiege the bay every day, and their wealthy passengers use the short shore leave of a few hours to visit the “Grotto of the Apocalypse” and the St. John’s Monastery. Halfway up the mountain, the tourist buses make their first stop at the Monastery of Revelation (Monítis Apokálipsis). The real interest is not in this 17th century monastery, but in the “Grotto of the Apocalypse”, which can be reached via forty high steps. According to legend, it marks the place where the Evangelist John asked his disciple Próchoras to write down a divine revelation (Apocalypse). To this day, in chapter 9, verses 3 and 4 of Revelation, one can read: “From the smoke gushed clouds of locusts, which fell over the earth, irresistible like scorpions. You had orders To spare the grass, the greenery and all the trees of the earth, but to attack the people who did not have the mark of God on their foreheads. Their mission was not to kill them, but to torture them for five months (…). «This last book of the New Testament is still today the source of the most varied of interpretations and the subject of passionate arguments because of its difficult to understand hints and threats.

For those who are more oriented towards the visible and tangible, two niches framed with silver are presented in the grotto. John is said to have laid his tired head in one of them during rest times, and in the other he is said to have leaned his hand while dictating. A large, three-column crack in the rock ceiling is still interpreted today as a sign of God’s Holy Trinity.

According to mathgeneral, the St. John’s Monastery, which appears defensible to the outside world, was founded in its origins in the 11th century by the abbot Christódoulos, and is the dominant structure of Chora. Next to the monastery courtyard, which is lined with colored pebbles, rises the cross-dome building of the Katholikons, the main church of the monastery. With its wall paintings, which date back to the 12th century, this church building is certainly one of the special “art-historical pearls” of the complex. The treasury of the monastery, which is accessible from here, and the library founded by the abbot Christêdoulos with thousands of manuscripts and books are generally not allowed to be entered. However, the museum with its icons, manuscripts and liturgical implements offers an insight into the treasures of the monastery that have accumulated over the centuries.

The mostly whitewashed houses on the narrow streets of the town of Chora, which was founded around the monastery in the 15th century, appear self-contained and almost a bit like a fortress from the street side. No wonder in view of the repeated pirate attacks and looting of the island at that time, which sometimes brought Patmos to the brink of economic ruin.

But despite all the innovations, parts of the medieval Byzantine appearance could be preserved here as well as in the monastery, which captivates the visitor while strolling through the narrow, partially vaulted alleys and the small squares. The mighty patrician houses in the old town bear witness to the wealth of the monastery and the island’s merchant fleet, which comprised 40 ships at the beginning of the 17th century. With the rare glimpses into the cozy, flower-covered inner courtyards and the sight of the architecture characterized by wood and ceramic elements, you get an idea of the former living culture of wealthy captains and traders on Patmos.