Before the current one, the Italian peninsula had other names: Tirrenia, Ausonia, Opica, Esperia and Enotria. Later the name of Italy prevailed, it seems, from an Umbrian word “vitlus”, which means veal. And this is to signify the abundance of cattle in the country.

At first Italy was called only the extreme point of today’s Calabria, whose inhabitants were called Itali; then, when Rome conquered the whole country, the name spread throughout the peninsula.

From the findings made in several caves it was possible to deduce that the village was inhabited since the most remote ages and the remains of the villages on stilts, found especially in the Po Valley, gave the opportunity to get an idea of the homes of those peoples. But precise information of the prehistoric peoples has not reached us.

Instead, the passages of all the most civilized populations that lived in Italy in antiquity, first of all those of the Etruscans, who settled in present-day Tuscany, are very documented. See Countryaah for population and country facts about Italy.

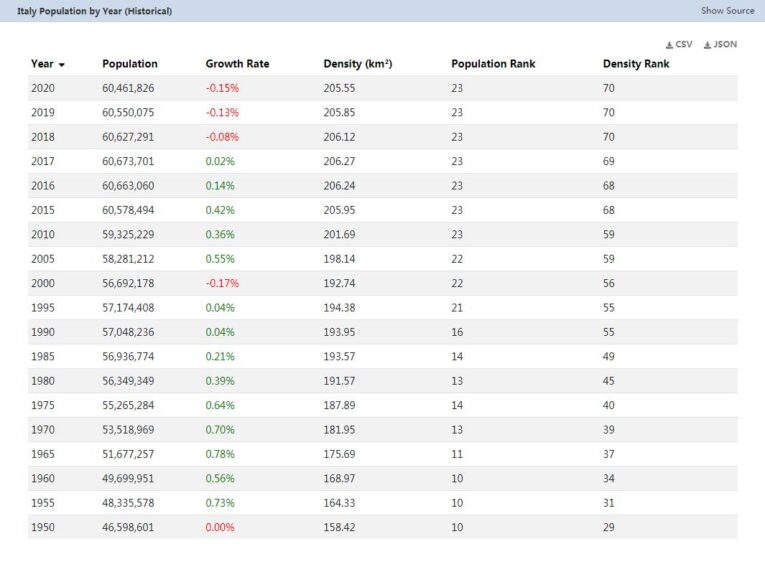

Population development

In the 17th century, almost 11.5 million people lived on what is now Italy’s national territory. The population grew rapidly from the 18th century. Despite the great loss of emigrants, the population almost doubled from 26.3 million to 50.6 million between 1860 and 1960. Since that time, however, population growth has been extremely low. The population has only increased by around 7 million since 1960. A further decline in birth rates is to be expected in the future, a trend that is increasingly becoming apparent in southern Italy, which used to be a booming region.

Furthermore, until the mid-1970’s, poverty, unemployment and high birth surpluses in the less developed south were the causes of a large number of emigrations. Malaria, which was rampant in southern Italy until the turn of the century, intensified this trend in the affected coastal areas.

In this way, over 10 million Italians have left their homeland within 100 years. Many went to North America. But Italians are also among the first generation guest workers in many European countries.

There is also ongoing heavy internal migration in Italy . Their directions go from south to north, from the mountains to the plains and from the countryside to the city.

Almost two thirds of the population live in cities. a. in the megacities of Rome, Milan, Naples and Turin. The urban regions in northern Italy take up less than ten percent of the total national territory of Italy, but are home to a quarter of the total population and about half of the manufacturing industry.

Population distribution

The country’s population is very unevenly distributed.

The coastal areas and the plains in the north are very densely populated, the inner mountainous country, the south and Sardinia, however, are much thinner.

In the 8th century BC, long before the foundation of Rome, many populations of different origins inhabited Italy. In Lazio, from the Latin “Latium”, that is an open place, region located along the lower course of the Tiber, the Latins settled. And then again there were the Ligurians, the Sardinians, the Siculi, the Apuli, the Venetians, the Umbrians, the Equi, the Osci, the Rutuli, the Volsci, the Samnites, the Bruzzii and the Sabines.

The founders of Rome (753 before Christ) were, in fact, called Romans. They conquered all of Italy: the Volsci, the Equi and the Etruscans in the fifth century BC; the Samnites in the IV and the Greeks of Magna Grecia in the III.

The events of Rome

With the subsequent victories over the Gauls (222 BC) and the Carthaginians (201 BC), the Romans then went as far as Sicily, Sardinia and Corsica. From then until 476 after Christ, the date of the fall of the Roman Empire, the history of Italy is identified with that of Rome, which was glorious and which brought its great power to a large part of the world then known.

With the fall of the Roman Empire, the Italian peninsula was subjected to the barbarian invasions, which began since 4th century after Christ. From 476 to 493 it was ruled by Odoacre, king of the Eruli; from 493 to 526 ruled Theodoric, king of the Ostrogoths and his successors.

In 553 Justinian, emperor of Byzantium, freed Italy from the Ostrogoth barbarians, but after only 15 years the Lombards arrived and led to the division of the peninsula into two parts: one under the Longobards and one under the Byzantines. And so it remained for more than a millennium.

Italy became a land of conquests. nell ‘VIII was the scene of a long war between Lombards and Franks (inhabitants of present-day France) who in 774 conquered the central-northern part. From 800 to 814 these territories were part of the Holy Roman Empire founded by Charlemagne, king of the Franks. From 827 to 878 still a foreign invasion occurred in Sicily, which fell into the hands of the Arabs, coming from Africa and victors over the Byzantines.

So towards the end of the ninth century Italy was divided between Lombards, who occupied the Duchy of Benevento, Franks, Arabs and Byzantines, who still owned some ports of Puglia, Calabria and the Duchy of Naples. In addition there was the state of the Church which dominated the areas corresponding to the current Umbria, Marche and Lazio.

On the death of Charlemagne, which took place in 814, the whole area included in the Holy Roman Empire became independent and constituted the Kingdom of Italy.

For 74 years at the helm of this kingdom, great Italian feudal lords took turns but none of them ever managed to have supremacy over the others and, often, still divided into small fiefdoms, they fought each other weakening more and more. This convinced the emperor of Germany, Otto I, to cross the Alps with a large army to occupy the Kingdom. And in 962 he was crowned emperor of the Holy Germanic Empire and king of Italy.

Shortly after 1000, in the south of the peninsula it was formed another great empire, that of Normans, who chasing away the Lombards, the Byzantines and the Arabs, conquered Sicily, Calabria, Puglia and Campania.

But these German emperors, having to deal with the affairs of their countries, could not always pay so much attention to the kingdom of Italy. Some cities in the north took advantage of this to free themselves from the foreigner and created entities, which they called “Municipalities”, determined to fight to the death to gain independence.

In the twelfth century the municipalities succeeded in the enterprise. Very famous was the battle of Legnano in 1176 fought and won against Federico Barbarossa, emperor of Germany.

In 1186 Barbarossa managed to carry out the marriage between his son Enrico and the princess Costanza, the only heir of the Norman Kingdom. Four years later, on the death of his father, Enrico assumed the title of Emperor of Germany and King of Sicily and Puglia.

Germanic rule lasted until 1266 when Charles of Anjou, brother of the king of France, seized the kingdoms of Sicily and Puglia, undermining the Normans. But the Angevins were not good rulers and soon a great discontent was created among the people, especially in Sicily. And in 1282 in Palermo he broke a great uprising of the people, passed into history as the “Sicilian Vespers”, because it exploded at the hour of vespers. Soon this revolt took on a real war character. The Sicilians asked the Aragonese for help, who helped hunt the French but occupied the place. Sicily was once again under the rule of another foreigner.

Meanwhile, the municipalities, after winning the fight against the Germanic foreigner, fell prey to internal struggles, always for the thirst for power. Families of the same municipality fought among themselves for the possession of the highest offices, resulting in a great disorder everywhere. To remedy this state of affairs, it was decided to entrust the government of each of these municipalities to a single man, as long as intact and charismatic, who, over time, was called “Lord” and, consequently, the municipalities they became “lordships”, that is, small absolute monarchies that became real monarchies. Among the most important families of Lords were the Visconti and the Sforza in Milan, the Medici in Florence and the Savoy in Piedmont. And since some of these gentlemen managed to obtain the title of “Prince”,

In Naples, meanwhile, in 1435, after twenty years of reign, Joan II died of the house of Anjou, without leaving heirs to the throne. A hard struggle immediately broke out between two contenders: Renato d’Angiò and Alfonso of Aragon.

The latter, helped by the Duke of Milan, Filippo Maria Visconti, defeated the Angevins and occupied Naples in 1442. In the reign of Naples then the French replaced the Spaniards.

Towards the end of the fifteenth century Italy was divided into two parts: one part under foreign domination and the other consisting of many small states, often at war with each other.

But this certainly not enviable political situation was opposed, however, by the cultural one that brought Italy to the head of all the other European states. In literature, the most shining star was Dante Alighieri, with Francesco Petrarca and Giovanni Boccaccio, as well as many other minor areas. In the figurative arts they excelled Cimabue, Giotto, Masaccio, Donatello, Perugino and Michelangelo Buonarroti, and the supreme Leonardo da Vinci. In the field of exploration the name of Christopher Columbus shone. Furthermore, thanks to the flourishing trade practiced by the rich Maritime Republics of Venice, Genoa, Pisa and Amalfi, established in the tenth century, and by the banks of Milan and Florence, Italy was one of the richest countries in Europe.

The political situation of Italy in those times was, as mentioned, clearly negative. Therefore, the then king of France, Charles VIII, did not escape the possibility of conquering the peninsula with ease and being able to gain an outlet on the Mediterranean.

In 1494, with the complicity of all the leaders of the central-north Italian states, which in fact did not oppose any resistance, and on the pretext of wanting to regain the kingdom of Naples, he entered Italy and the following year, almost without encountering obstacles, succeeded in the enterprise.

While Ferdinand of Aragon took refuge in Ischia, some Italian princes, convinced by now that they had not shown decorum and character when they sent Charles VIII through, decided to join a league to drive him out of the territory with all his soldiers. The French king, having assessed the situation, decided to abandon the camp and resumed his way back.

In Fornovo, on the Taro, in 1495 the armies clashed and after a hard battle, won by the French, Charles VIII managed to pass and return to France. Meanwhile Ferdinand of Aragon had taken over the throne of Naples.

On the death of Charles VIII, which took place in 1498, his successor Louis XII, seeing that the league of Italian princes had dissolved, retried the enterprise. And this time, however, Spain took the field, which had the upper hand. The situation that followed was that the kingdom of Naples was firmly in the hands of the Spaniards while the Duchy of Milan, driven out Ludovico Sforza, called the Moro, was firmly in the hands of the French.

In 1559 France and Spain signed a peace treaty in Cateau-Cambresis following which two thirds of Italy passed into the hands of the Spaniards.

During the Spanish domination, the worst ever endured, Naples was always in the midst of epidemics, famines, miseries and bad governance. There were many popular revolts; the most violent one occurred in 1647 and was cruelly sedated.

While these events followed, another Italian state, the Duchy of Savoy, comprising Piedmont and Savoy, had always remained autonomous. He had excellent rulers, such as Emanuele Filiberto, Carlo Emanuele I and Vittorio Amedeo II. The latter enlarged his state and obtained the title of King of Sardinia in 1720.

In the first half of the Eighteenth century Europe was devastated by many wars, in which the most powerful states of that time took part: Spain, France, Poland, England, Holland and Russia. At the end of these wars, in 1748, Italy was almost entirely under Austrian rule. The southern one and Sicily passed to the Bourbons. The only state that remained independent was the kingdom of Sardinia, made up of Sardinia, Piedmont and Savoy.

At the end of the eighteenth century a great event shocked France: the French Revolution. It arose from the serious situation the people were in, harassed by the nobility and poorly governed by an inept monarchy. And this revolution that preached brotherhood, equality and freedom was also the beacon that awakened the desires for freedom of many submissive and repressed peoples around the world.

The history of France, after the period of unrest, beheadings, of Robespierre, saw a star of unusual size shine forth: Napoleon Bonaparte. Young Corsican general, after leading and winning many wars in Europe, he then suffered defeat in 1815 by the powers of Austria, England, Prussia and Russia. These decided to give a new order to Europe. And as far as Italy is concerned, it found itself once again divided into many small states, all directly or otherwise subject to Austria. The Lombardo-Veneto was considered even Austria.

But Austria, however, did not take into account that times, especially with the dictates of the French Revolution, had changed a lot and people wanted to be free. Thus the Italian patriots, unable to express themselves openly, on pain of the very serious retaliation of the Austrian police, formed secret associations, among which the best known were the “Carboneria” and the “Giovine Italia”, the latter founded by the Genoese patriot Giuseppe Mazzini..

From 1820 to 1844 the followers of the secret societies staged many demonstrations and riots. All tamed and many of those arrested were sentenced to death. The Italians were increasingly convinced that Italy had to be freed from the Austrians. On March 4, 1848 a decisive turning point occurred in the history of Italy. Carlo Alberto, king of Sardinia, in addition to granting the Constitution, also decided to place himself at the head of an army to fight the Austrians.

That was the year in which many popular revolts took place in Europe, both for autonomy and for wider participation in the government of their states. In the afternoon of March 17, 1848, the echoes of the riots that occurred in Vienna reached Milan. The Milanese patriots, who had been organizing a revolution for some time, understood that the moment was propitious and decided that the following day they would gather for an initial demonstration, in front of the Government Palace, in Via Monforte. The guards, upon the arrival of the demonstrators, fired on them in an attempt to intimidate them and make them retreat. It was not so, on the contrary, that episode started a real war, fought with few means but with a lot of determination by the Milanese people, against a highly organized and preponderant Austrian army. Five were the famous days in Milan; at the end of them the Austrians, commanded by General Radetzky, abandoned Milan to the Milanese. And on March 23, in the aftermath of the 5 days in Milan, Carlo Alberto declared war on Austria.

For the occasion Giuseppe Mazzini returned home from South America with a group of volunteers and everything was ready for the rescue. That there was not. Austria was too powerful and exactly one year after the beginning of the war, on 23 March 1849 Carlo Alberto, after suffering a serious defeat in Novara, abdicated in favor of his son Vittorio Emanuele II, and went into exile in Porto in Portugal, where he remained until his death. The Austrians returned as masters to the Lombardy-Veneto region. We had to start all over again.

The new king, assisted by his highly skilled minister Camillo Benso count of Cavour, who truly was the architect of the unification of Italy, worked tirelessly for a decade and finally, at the beginning of 1859, he was able to reach the alliance with Napoleon III, emperor of the French. On April 29, 1859 military operations began against the Austrians, who were clearly beaten. On 11 July 1859 the armistice of Villafranca was signed with which Lombardy was annexed to the reign of Vittorio Emanuele II. And as these events unfolded, another important fact occurred in the states of central Italy. Even in Tuscany and Emilia-Romagna the populations asked to be part of the kingdom. So that most of central and northern Italy was unified.

It was necessary to intervene in the south where Francis II of Bourbon was comfortably seated on the throne of the two Sicilies, who reigned under the directives of Austria.

And this was another great hero in history, not only from Italy, who was Giuseppe Garibaldi. He, in no time, gathered a thousand volunteers to embark on what exactly went down in history with the name of “Expedition of the Thousand”. With two ships, “Piedmont” and “Lomardo”, owned by the Rubattino Company, the Thousand left on the evening of May 5, 1860 for Sicily, where thousands of patriots were already waiting to join them to drive out the stranger.

At dawn on 11 May Garibaldi and his red shirts landed in Marsala and began their march. One of the toughest battles in this venture was that of May 15 in Calatafimi. Throughout the day the Garibaldi soldiers fought against the Bourbons with great fury and in the evening the city was conquered. In just 4 months Sicily and the Neapolitan were freed. Given the great success Vittorio Emanuele II, at the head of his army, he started to occupy the Marche and Umbria, then went to meet Garibaldi, in Teano. On February 18, 1861 the Kingdom of Italy was proclaimed and Vittorio Emanuele II was its king. But Italy was not all. Rome, Venice, Trento and Trieste were missing. Roma and Lazio belonged to the Papal States and the three cities of the Veneto were still in the hands of the Austrians.

An attempt was made to peacefully define the question of Rome. Bettino Ricasoli, who succeeded Cavour, tried everything by diplomatic channels, but without success. Garibaldi then thought of leaving Calabria with a group of volunteers and heading for Rome; but he was stopped by the king, convinced as it was that the pope, Pius IX, would ask France for help, which would then certainly declare war on Italy.

For Veneto, on the other hand, the company could be accomplished with less difficulty. Italy was able to count on the help of Prussia who, fearing Austria’s overwhelming power, proposed an alliance to fight the common enemy. And on June 15, 1866, at the end of the conflict, the Veneto passed into the hands of the Italians, but not Trento and Trieste who remained in Austria.

1870 was the decisive year to also define the question of Rome. France found itself at war with Prussia and had withdrawn its army from the Papal States. To Vittorio Emanuele II it seemed a magnificent opportunity to attempt the conquest of Rome. In fact he succeeded because Pius IX did not want him to shed blood unnecessarily and, after a slight resistance, he gave in to the king’s army. On September 20, 1870 Rome was proclaimed the capital of Italy.

The three great characters of the Italian Risorgimento, as well as of course Cavour, died: Mazzini in 1872, Vittorio Emanuele II in 1878 and Giuseppe Garibaldi in 1882.

Umberto I ascended the throne of Italy, who immediately found himself facing a difficult economic situation, created by the continuous wars. Thus, given the companies of other European nations, also supported by his ministers, colonial conquests began. Thus it was that in 1885 Eritrea came and Somalia in 1889. At least economically there was some breathing space as many citizens, without work at home, moved to the colonies, where industries and businesses also started.

From 1903 to 1914 Italy, led by the skilful minister Giovanni Giolitti, experienced a good period of prosperity. In 1912, following a victorious war against the Turks, Italy found yet another colony: Libya.

And in 1914 the First World War broke out in Europe. Italy initially declared neutrality but then, given the possibility of conquering Trento and Trieste, entered the war against Austria. After three years of hard struggle and with the loss of many human lives, Italy was among the winners and with the Treaty of Versailles of 1919 it was able to regain Trentino, South Tyrol, Trieste and Istria. And this made Italy a truly united, free and independent state.

Of course, however, this long war had weakened the country’s economy, which was the scene of strikes and unrest until in 1922 a man came forward who declared he was able to restore order and well-being. This man was Benito Mussolini, a former socialist, who had founded his own party: “fascism”. He had, from the then King Vittorio Emanuele III, the task of forming a government and soon Mussolini showed his true intentions, that is, to govern the country as a dictator. Nationalist to the bitter end, he got rid of all his political rivals, he also isolated himself economically from other countries, proclaiming autarky. One of the companies of this type was the famous “wheat battle”, which began in order to improve and increase production, to be self-sufficient.

In 1936 he began a policy of territorial expansion going to occupy Ethiopia and in 1939 he invaded Albania. Vittorio Emanuele III was thus King of Italy and Albania and Emperor of Ethiopia. In reality he was a rather manageable individual, unable to counter the dictator who, therefore, made good and bad weather. And when World War II broke out in 1939, Mussolini wanted Italy to join forces with Hitler’s Germany, also a sadly known dictator. This alliance was the ruin of Italy. At the end of the disastrous and inhuman conflict Italy, also subjected to Nazi domination, defeated, half destroyed by bombing, full of misery, unemployed and many other ills, lost all the colonies and had to give up much of Venezia Giulia to Yugoslavia.

From 1946 following a popular referendum, Italy became a Democratic Republic.

Provisional head of the state was Enrico De Nicola. On 12 July 1946 the task of forming the government was entrusted to Alcide De Gasperi, who launched one of the coalition between the three major parties, the Christian Democrat, the Socialist and the Communist, with the accession of the historical republican.

In reality two distinct blocs were formed immediately, on one side the Christian Democrats and on the other the Communists, while the Socialists, who also proved to be the second party in the nation, had to content themselves with a secondary role, almost dependent on the party Communist. This did not please some followers who contrasted the policy of their leader, Pietro Nenni, and made a split. Thus was born the Socialist Party of Italian Workers, led by Giuseppe Saragat.

De Gasperi made a trip to the United States in January 1947 and resigned on his return. In February he was again commissioned to form a new cabinet. He therefore asked for Saragat to join. But not having obtained it, he repeated his resignation. In May, then, he managed to form an all-Christian government with some independent, and vice-president of the council was Luigi Einaudi. Then the Saragat party and the Republicans, in December 1947, entered the government and their leaders Saragat and Pacciardi intervened to assist Einaudi.

On December 22, 1947 the new Constitution was approved, signed on the 27th by Enrico De Nicola, who from provisional became the definitive President of the Republic. On the 28th the former King Vittorio Emanuele III died in Alexandria in Egypt.

Italy threw itself headlong into the reconstruction of the country, which proceeded with alacrity and success, also as a result of the continuous and substantial American aid. But in the meantime the Peace Conference, which Italy was not only not admitted to, but despite all the great diplomatic efforts supported by De Gasperi, received rather punitive treatment. Italian cities such as Pula, Rovinj and Porec, Rijeka and Zadar had to be delivered to Yugoslavia, protected by Russia. Trieste was then proclaimed “Free Territory”. Moncenisio, Briga and Tenda were sold to France. The Dodecanese returned to Greece. Italy also had to compensate the war damage to Yugoslavia and Albania,

The elections of April 18, 1948 gave an absolute majority to the Christian Democrats. In May Einaudi became President of the Republic and De Gasperi formed the new government, roughly like the previous one. 1948 ended without major upheavals. The only major episode was the attack on Palmiro Togliatti, leader of the communist party, which took place on July 14, 1948. And then commercial and friendship treaties were concluded with other countries.

On April 4, 1949 Italy signed its entry into the Atlantic Pact. On the basis of this, it was possible to ask for the solution of some problems left on the carpet since the end of the war; first of all that of Trieste and then that of the colonies. After much negotiation, Italy only obtained the administration of Somalia for ten years.

On January 14, 1950 there was a government crisis due to conflicts between the left and right currents of the Christian Democrats themselves. The new government was a center-left “tripartite”, all tending towards major social reforms. For the improvement of the economy in the south, the “Cassa per il Mezzogiorno” was set up.

In January 1951 elements of crisis intervened within the Italian socialist party. That of the Italian workers joined the unitary socialist party, formed previously, and changed its name to that of the Italian Democratic Socialist Party. After this union came out of the government. De Gasperi should have dissolved the cabinet but, in consideration of the proximity of the administrative elections of the future May-June, he made a simple reshuffle and led the legislature to port. At the administrative offices of June 1951, the Christian Democrats underwent a downsizing while the far-right and far-left parties experienced a certain development. The resulting government was of a democratic alliance.

In June 1952 Giuseppe Romita was elected to the top of the new socialist party while in the same year Italy signed a treaty in Lisbon for the “European Defense Community” and then a tripartite pact with the United States and Great Britain which allowed the entry of some Italian administrators into the free territory of Trieste, in view of the forthcoming return of the city to the motherland. Towards the end of that year the effects of all the social reforms carried out by De Gasperi began to be felt. However, after the administrative elections of 1953 ended, he had to be replaced by Attilio Piccioni. But he too was unable to form the government. And then in August Einaudi entrusted the new task to Giuseppe Pella, Minister of the Budget, who formed a government of “technicians”, supported by some qualified independent. De Gasperi, who in the meantime had become Party Secretary, suggested to Pella the names of the ministers who should have been present in the government and since Pella did not accept these suggestions the government fell on January 4, 1954. Another exponent of the Christian Democrats was called to form the new government; this was Scelba who formed a “quadripartite” bringing together the 4 center parties.

In June 1954 the Congress of the Christian Democracy was held in Naples which assigned the party secretariat to Amintore Fanfani. De Gasperi, who recently became President of the National Party Council, died on August 19, 1954. In September the government suffered another crisis, due to the forced resignation of the Foreign Minister, Piccioni, and Scelba had to reshuffle and in October Trieste returned to Italy, so that the central government coalition strengthened.

In April 1955 new presidential elections were held and Giovanni Gronchi, an exponent of the Christian Democrat left was elected President. The Scelba government was resigned and another Christian Democrat Antonio Segni was appointed. During his government a period of tranquility was experienced and in December 1955 Italy became part of the United Nations.

Meanwhile, a better understanding between the parties in the center was emerging within the country, while the opponents suffered a certain regression, both on the right and on the left. An incurable rift emerged between the Communist and Socialist parties after the events of Hungary.

In May 1957 there was a sudden crisis and Saragat left the government, followed by the Republicans. The legislature was however completed by a single-colored cabinet. In the same year, a treaty was signed in Rome for the establishment of the “European Economic Community”.

The Christian Democracy in the elections of May 1958 was considerably strengthened and Fanfani formed the new coalition government. In foreign policy at that time Italy saw its prestige increase for having conducted good mediations especially in affairs concerning the Middle East. But internally, after some difficulties arose, on January 26, 1959 the government resigned and Antonio Segni was called to form another, which was launched by a large majority of Christian Democrats, because it could count on the support of the liberals and the rights. Pella returned with the post of Foreign Minister and reiterated Italy’s presence in Atlantic politics. In the meantime, after a Congress, the Christian Democracy had appointed Aldo Moro as Secretary General, with the support of Giulio Andreotti and Antonio Scelba.

In February 1960 the liberals took their support from the Segni government and he was forced to resign. Democratic groups, however, hastened to support a single-colored Christian Democrat government again chaired by Fanfani.

In November 1960 the return to democracy was confirmed by the administrative elections.

In the year 1961 the government faced various problems related to improving the economy and social reforms. The implementation of the regions, the revision of the agrarian pacts, legislation for urban planning and building areas had to be carried out but in particular the nationalization of electricity had to be considered, insistently requested by the socialists. In 1962, after Giovanni Gronchi’s term expired, Antonio Segni was elected President of the Republic.