From historical research and archaeological excavations carried out in Albania it has been found that the materials found are similar to those of southern Italy and this indicates that the relations between these two countries were intense, more than those with the neighboring territories.

There were certain migrations from Albania to the coasts of the Salento Peninsula, the Messapi, the Peucezi and the Iapigi.

At the time of the division of the Roman Empire into two parts, the area of present-day Albania was called Praevalitana and this was dependent on Byzantium. And since it was divided into many small ladies, part of them remained united with the Serbian and Bulgarian states, part joined to the Venetian domains and still part to the Angevins of Naples.

In 5th century in Albania the Goths dominated; their king, Ostrojla, also proclaimed himself king of the Praevalitana. Justinian, in 535, reconquered the region bringing it back within the Byzantine Empire.

Other barbarians began to flow into the area: Ungari, Bulgari and Avari. But the most dangerous raids were those of the Slavs. As early as the 6th century, the Slavic Rutomir persecuted Christians. Its dominion was truncated by the Avars, who in turn were eradicated by the Serbs, even called by the emperor Heraclius. Since then, Serbian Principalities were formed, of which the most important were Montenegro, Lower Herzegovina and Dalmatia. These principalities were nominally dependent on the Byzantine empire but were actually independent. Byzantine lordship was practically limited to the coasts of Albania.

In 917 the king of the Bulgarians, Simeon the Great, came into possession of the whole of Albania, except precisely the coasts, which remained in Byzantium. And, first under the Bulgarian kingdom, then under the Macedonian one, Albania remained until 1019, then returned directly under Byzantium.

In the eleventh century there was an important turning point in the history of the country and it was the rapprochement of the region to the west. Relations with the Maritime Republics intensified, in particular with that of Amalfi who even founded his own young lady in Durres. But above all, there were close ties with Angevins, Swabians and Normans who made political, economic and moral relations between Albania and Italy stronger.

Even the Republic of Venice in this period made a clear penetration in the Albanian territory. Among other things, the introduction of the olive tree in the village is due to it. The influence of the Serenissima developed mainly in the thirteenth century. With the Fourth Crusade, instead of freeing the Holy Sepulcher, Venice conquered, at least nominally, all of Albania and Epirus.

However, various feudal lords arose which, headed by Michele Angelo Comneno, prevented Venice from taking practical possession of the Albanian lands.

In 1230 the Bulgarian Empire of Tsar John Asjan II came; then came the lord of the Serbs who reached maximum splendor with Stefan Dusan, who reigned from 1331 to 1355, with the name of Tsar of the Serbs, Greeks, Bulgarians and Albanians. After this empire, others took turns who saw Venetians and Angevins on the field until the Turks arrived. Then in Albania one of the greatest defenders of Christianity stood out: Giorgio Castriota (Scanderbeg). He brought together all the people of his race to fight Islam. The “League of Albanian Peoples” was founded. And, when in 1454, Castriota refused an offer of peace made by Muhammad II, chief of the Muslims, this, very skilful deceiver, tried to cross paths and managed to bring some of the Albanian allies to his side. Fierce were the struggles that however ended the death of Castriota,

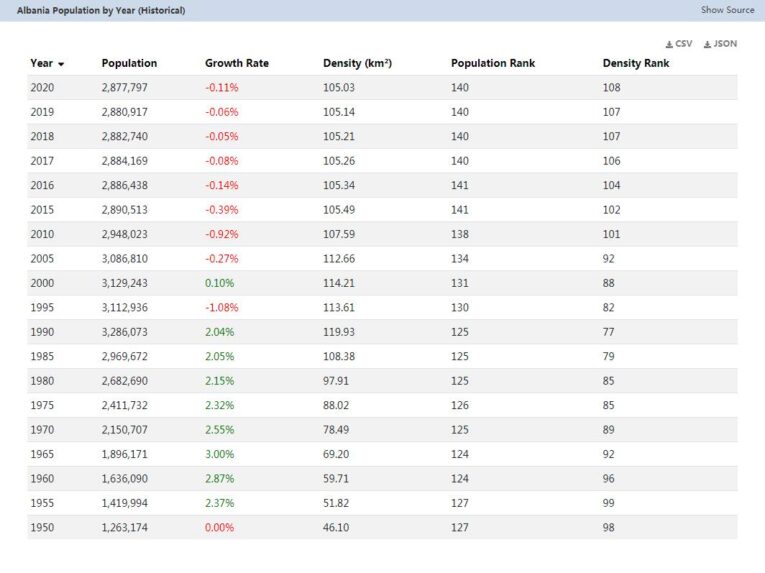

But the epic of this hero was at least capable of curbing the expansionist aims of the Ottomans in Europe. They remained undisputed lords in Albania, but many Albanians fled to southern Italy and settled there permanently. See Countryaah for population and country facts about Albania.

The Albanians, both from the north and the south, by accepting the conditions of peace imposed by the Ottomans, largely maintained their autonomy and were able to continue freely to profess the Christian religion. Instead in rapid central Albania it was the process of Islamization of the people. This part of the country was always divided into small autonomous principalities, which never had the possibility of redemption from the yoke. In the 16th and 17th centuries they tried to rebel, with the help of Venice and also of some popes, including those of the Farnese family.

But Islamism also breached some Albanian peoples, such as the Mirdites, whose leader, Marku Gjon, performed heroic deeds in the service of the Turkish army.

Certainly the fragmentation of the country was the main cause for which the Mirdites fought against their compatriots. In fact, there was little understanding between those peoples who always found themselves in the midst of rebellions, struggles and submissions. The Albanian peoples, although divided by hatreds, rivalries of lords, tribes, cities, always and only turned to Italy, especially in Venice and Naples, for help and this was always given to them and also with wide consent.

In the 19th century, under the auspices of Russia, the liberation movement of the peoples subjected to the Turks began. But the particular situation of Albania, divided between Muslims, Christians and Orthodox, made the undertaking very difficult. The Mirdites continued to fight alongside the Turks who remained to rule the country, despite the repeated rebellions and with two treaties in between, that of Santo Stefano and that of Berlin of 1878. In 1912 the Ottoman Empire granted privileges to the country, but these did not find application since in the same year, having started the war in the Balkans, the Albanian peoples found themselves divided about the position to be taken towards the Turks. In a short time the nine tenths of the Albanian territory were occupied by Serbs, Greeks and Montenegrins.

During this period a vast program of implementation of Albanian autonomy was carried out by Austria-Hungary and Italy. Both states were intensely interested in the country because of the various economic developments due to the thriving trade. Therefore they worked very hard for the constitution of an autonomous Albanian state and on April 10, 1914 a special International Commission approved the constitution of the Statute of Albania. This was elevated to Principality under the guarantee of the European powers. William of Wied was placed at the head of this principality.

Simultaneously with these events another fact occurred. In Gjirokastra there was an autonomous government headed by Zografos, the former foreign minister of Greece. The result was fierce struggles which resolved with real massacres. Meanwhile, William of Wied, renouncing the collaboration of the Control Commission, had appointed President of the Council of Ministers Turhan Pasha, a former Turkish ambassador to Russia. And the weakness of this government, the massacres of southern Albania by the Greeks, the rebellions of central Albania, were the main causes of the end of the Principality. The prince fled and the only power that remained in the country was that exercised by the Control Commission; but she also didn’t have a great chance to act because, in the meantime, with the outbreak of the First World War,

Italy, in the years that followed, had a preponderance in the occupation of the Albanian territory and the Italians were always greeted with great sympathy. But this sympathy failed when Italy, with the Italian-Greek agreement of July 29, 1919, recognized the Greek aspirations for southern Albania.

In 1920 the 25-year-old Ahmed Zogu, of an ancient Mati family, appeared on the Albanian political scene. In 1921 he was Minister of the Interior; in early 1924, while climbing the stairs of the Parliament Building, he was injured by a student, Beqir Valter. He took refuge temporarily in Yugoslavia and in December 1924 he returned to his homeland and re-assumed power, obtaining remarkable results.

He reconstituted an army, trained by Italian officers; for the first time in Albania he created a small navy, also organized by an Italian officer; instituted the National Bank of Albania and a currency, all Albanian, the “lek” which immediately replaced all the other currencies previously circulating. To this same bank he entrusted the task of taking care of trade with European nations. Then Zogu financed reclamations, road works, the construction of various public buildings and the Durres-Tirana railway, as well as port works in Durres and San Giovanni di Medua.

He then rearranged the customs and tax services; made special concessions for the best exploitation of state-owned forests; set exact rules for oil concessions; he developed more modern means for education and health. In each province, the first instance courts were established with three judges and a Court of Cassation, with 6 judges in Tirana, the capital. Administratively Albania was divided into nine provinces: Durres, Shkoder, Corizza, Elbasan, Tirana, Gjirokaster, Berat, Kosovo, Dibra. Freedom of worship was left with three religions: Catholic, Orthodox and Muslim.

Of course, to carry out such a vast and important program, Zogu had to apply an iron regime and had to prevent some classes from perpetrating abuses. And all this always through severity measures. For foreign policy, Zogu turned more towards Yugoslavia at first. But following some negative episodes, he had to revise his positions and on November 27, 1927 he signed a friendship and security pact with Italy. With this agreement, the two states agreed on mutual aid in the event of external attacks.